The Five Personality Traits

OCEAN: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism

Over the past couple months, I met some new folks and got to spend more time with family than I normally do. It was the holidays, after all. This gave me an opportunity to think more about personality traits, and the age-old question of nature v.s. nurture.

How much of our character is inherited? How much is developed as a reaction to our environment? Can personality change over time? Is there such a thing as a personality type? Are there some traits that are better than others?

The urge to classify people according to types is very natural, and goes back some thousands of years. The Greek physician Hippocrates is of course known for expanding on the four temperaments, various bodily fluids that influence character: sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic.

There are several modern personality tests, too–including the Myers-Briggs test, which classifies people into 16 different personality types, and the Enneagram, which classifies people into 9 different types.

These are mostly based on unfounded science, however. The reality is that there are no distinct types of people.

Every person is instead a unique combination of at least five different positions on a spectrum. A person’s position on any of the five spectrums can range from 0.1 to 99.9% – it’s not a binary thing.

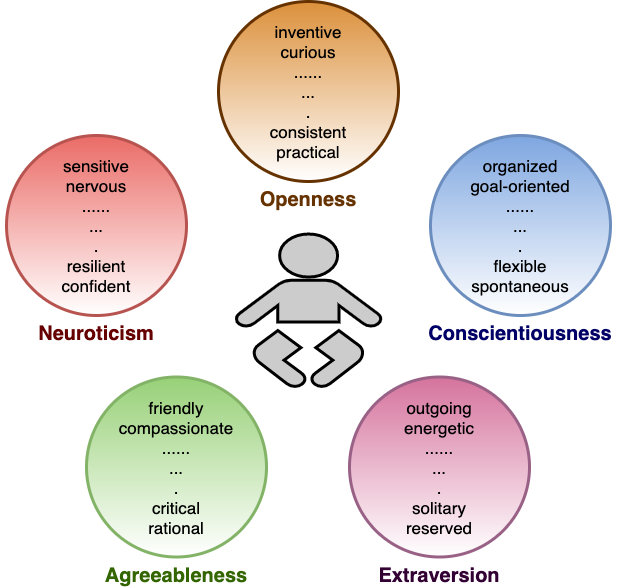

The five spectrums or traits spell out the acronym OCEAN:

- Openness

- Conscientiousness

- Extraversion

- Agreeableness

- Neuroticism

It’s important to keep in mind that your position on each spectrum is intrinsically neither good nor bad. Being closer to either end of one spectrum has its advantages and disadvantages.

For example, someone with a high score on the openness spectrum would be more likely to grasp abstract ideas, be creative, and engage in self-examination. But someone with a low score might be more consistent, traditional, and practical.

Someone with a high score on the conscientiousness spectrum would be more dutiful, organized, and persistent. They are more likely to make a plan and stick to it. Someone with a low score, on the other hand, might be more spontaneous, flexible, and extravagant.

A high extraversion score would imply being excited about (and probably good at) engaging with the external world, including people, outdoor activities, and social settings. A low score would allow someone to maximize gains from solitary endeavours, with a better ability to focus on an internal, controlled environment.

The agreeableness spectrum relates to your ability to get along with others. A high score means you are interpersonally easy going, and like to make sure those around you are happy. A low score, however, means you are more critical and willing to question others when you think they are wrong.

Finally, people with a high score on the neuroticism spectrum are more likely to respond to stressors with some kind of negative emotion like anxiety, sadness, anger, guilt, or fear. They are more likely to have low self esteem and experience depression.

Someone with a low neuroticism score, on the other hand, is more likely to brush off negative events and just move on. They are more resilient and tend to be more confident.

Neuroticism might have allowed our ancestors to survive in hostile environments, since neurotic people are primed to expect worst case scenarios. That’s why neuroticism can be seen as an evolutionarily beneficial trait passed down from our nomadic days when tigers, snakes or lions could jump out from anywhere at any moment.

In a comfortable and safe, modern environment, however, neuroticism seems to be more of a liability. More neurotic people are more likely to develop mental disorders, and their tendency to imagine unwarranted dangers can end up limiting and self-sabotaging them, personally and career-wise.

Although neuroticism is therefore typically viewed as an undesirable trait in modern life, there is some evidence to suggest that in certain highly competitive situations, it can lead people to higher levels of achievement–because the fear of failure motivates them to take on above average workloads. But that requires learning to manage and harness that neuroticism to productive use.

So how much of where you are on these five spectrums is inherited, and how much is based on the environment you were raised in? It’s about half and half. We inherit a more limiting range (e.g. 20 to 40% on Openness, etc), but where we end up within this limited range is based on our early childhood experience.

And people change over time, too. No matter where we currently stand on those five spectrums, the average person increases in agreeableness and conscientiousness, and decreases in extraversion, neuroticism, and openness.

Age does bring along some sense of maturity and wisdom.

The beauty of exploring these ideas (and here I speak as someone with a high score on the openness spectrum) is that it allows you to be more understanding and compassionate towards both yourself and others.

Where you stand on each spectrum does not matter from an intrinsic standpoint, but being aware of your position might help you be kinder to yourself, and might also help you better relate and respond to others.

My religious upbringing made me value conscientiousness and agreeableness so much that I thought that these were virtues, and that people who lacked them were somehow less deserving of God’s love or blessing.

But their polar opposites can also be virtues. Understanding context, and when to restrict your natural impulse, is key.

If you want to test yourself, Truity has a free test you can take in less than five minutes. No need to create an account or enter an email.