Mastery-Based Learning in the Age of Social Media

The Antidote To Today’s Barrage of Information

I have a confession to make. I’m an addict. I love everything about–and can never get enough of–learning. I keep coming back for another hit, over and over again. I’ve been doing it for over 30 years.

Everyone reading this knows what I’m talking about. Learning is probably the single most defining characteristic of human beings–it’s our superhero power. Our ability to internalize an empirical process, to map out and comprehend the relational and structural components of an existential reality or discipline, allows us to domesticate and harness the very structures of the physical world itself.

Learning, in essence, makes us more powerful than the most powerful beast. Because we can learn, we collectively invest in teaching. Because we can teach, we can pass down knowledge from generation to generation. And, finally, because we can pass down information to our progeny, every generation can continuously expand the boundaries of knowledge and keep making our entire species smarter and with better and better tools–thereby, with more and more power.

Over a relatively very short timespan, our species has gone from being a third-rate primate that feasted on the leftovers of much stronger predators to flying higher than eagles and faster than falcons, walking on the moon, and developing nuclear weapons. It’s hard to imagine a swifter and more drastic transformation.

Well, that’s all fine and good, but what does this have to do with mastery-based learning?

Learning and Socialization

You see, learning and socialization inevitably go together. For hundreds of thousands of years, we all have relied on parents, on family, and on teachers from our tribe to teach us what we need to know to not just survive, but to hopefully thrive. We are inherently wired for reliance on others–for socialization.

It’s not only that socialization provides us with camaraderie and hits of the feel-good chemical serotonin. Because learning has been tightly coupled with socialization for so long, it means that we invariably look to others to tell us what to learn. We look to others to tell us what’s important and what we should strive for in life. We look to others to tell us what we should value and love, and what we should hate. We look to others to tell us what we should think, and what we should believe.

Why is this a problem? If this is how it’s always been for thousands of years, and if it’s what has allowed us to be so successful as a species, why question it now? For those of us who adopt a historical or religious perspective that says there’s nothing new under the sun, or some version of Solomon’s sagacious comment in Ecclesiastes 1:9, why is today’s world any different?

The Information Age

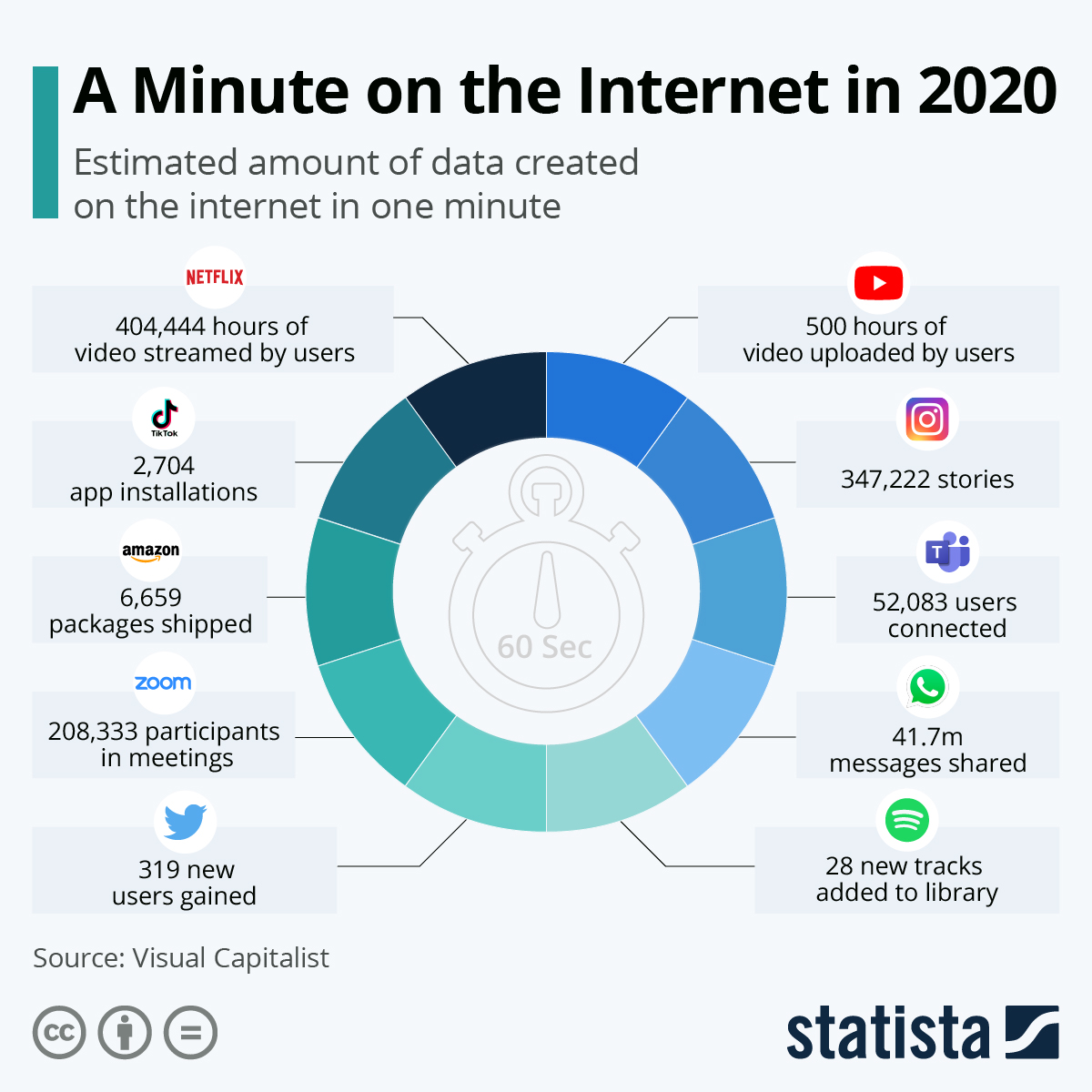

Much like many things in life, the answer has more to with a change in degree than a qualitative change. The scale, quantity, and speed of new information that we create and consume has gone from following a linear growth pattern to an exponential one. The culprit, of course, is the computer.

In developing the computer, the human brain has, at last, met its match. This is not to say that the computer can do everything that the brain can do–it cannot, or at least not yet. But by creating the computer, the brain has unwittingly unleashed a ubiquitous trap in which it easily ensnares itself–voluntarily or not–over and over.

The same intelligence that built the Internet and tools of instantaneous, boundary-less communication is also, unfortunately, highly susceptible to (and easily irked by) its own creation. Because of our dependence on others, we naturally care about what those around us do and what they believe. With access to smartphones and social media, we now have a bottomless supply and constant stream of social news, feeds, videos, and all kinds of updates that might be possibly relevant to our lives.

The brain has met its match, therefore, not in the sense that the computer is the brain’s equal, but in the sense that the brain easily succumbs to the unescapable distractions created by its own creation.

The biggest challenge we face in the information age–and it’s a challenge with as much relevance to politics as to education–is that our brain cannot adequately process the overwhelming amount of information, explicit and implicit, we are exposed to every day. Our brain helped us climb to the top of the food chain, but it now faces a hard time determining what’s important for us and what’s not. Everything somehow appears to be important, which means it’s very hard to prioritize.

Yes, it’s true that nothing of substance is new under the sun. The tiny kernel of truth we seek and actually need has remained constant, much like who we fundamentally are has remained constant. But the amount of ultimately unnecessary information we have to sift through every day to find this kernel is not only increasing–it’s accelerating. Separating the wheat from the chaff is becoming increasingly more difficult when the ratio of chaff to wheat increases at an exponential rate. And more difficult, still, when the chaff starts to look more and more like wheat.

This constant barrage of new information is specifically problematic for a learner on at least three main levels.

1. Distraction

Most obvious and often discussed is the sheer distraction that social media and the Internet present. This distraction perturbs and perhaps entirely disables the focus that the brain needs to be able to chunk new bits of information during the focused mode of learning. As much as we’d like to think we are good at multitasking, research shows we are actually really bad at it. Multitasking is especially incompatible with learning.

2. Buyer’s Remorse

While this issue of distraction is a serious problem itself, I would argue that there’s a second main way this never-ending stream of new information interferes with the learning process, and this second way is actually more dangerous and systemic, because it impacts students of all ages, abilities, and fields of learning.

As a whole, we are all now more confused than ever as we face more mental anxiety about what we should want and do with our time and, aggregately, with our lives. With a hundred thousand billion new books, shows, movies, services, websites, blogs, apps, YouTube videos, online courses, and social media accounts to choose from, to read, to download, to watch, and to follow, the learner now faces a significantly difficult choice even before settling down to actually learn anything.

What should I learn? What has value today and tomorrow? Whom should I learn from? Who’s the best teacher for this topic? How do I know? What do my friends recommend? What are other people learning?

The learner who proceeds without caution can easily get trapped in a vicious cycle of learning and second-guessing. Buyer’s remorse has never been more widespread. Even free content is not immune to this, because our time is itself very much limited.

3. Content Consumers

The third and last main way this barrage of information perturbs the learner is more abstract, but equally important because it also deals with identity and purpose, though at a different level. With so much content out there, it’s easy for us to perceive ourselves as (and assume the role of) consumers of content. Being a content consumer is easy. Going through an online course can coax you into thinking you are learning, but merely watching a video, for example, is actually just consuming content. Learning is much more difficult, because learning requires active participation. Learning requires adopting the mindset of a content creator, not a consumer.

What is the antidote? How can we find the wheat despite the much higher quantity of chaff we face?

The Antidote: Mastery-Based Learning (MBL)

The mastery-based approach to learning is more of a perspective and way of life than a prescription. What is mastery-based learning (MBL)? How does it solve the problems of the information age?

As succinctly as I can put it: MBL is about learning in order to become a master at a field, as opposed to learning in order to pass a test. Learning to pass a test is performance-oriented and creates a mental model that views learning as something that ends when the test is over, while learning to master a field is process-oriented and creates a mental model that views learning as a continuous duty that one maintains throughout life.

Sal Khan, the founder of Khan Academy, has an excellent ten minute TED talk about why mastery-based learning should replace test-focused learning in education.

As to how mastery-based learning helps solve or alleviate the problems of social media, let’s address them one at a time.

-

Distraction: When your goal is to master a field or discipline, you take responsibility for your journey. Yes, the distractions are still there and always will be. But because you know learning is a lifelong journey, a marathon and not a sprint, you pace yourself, and you practice every day–even if it’s just for thirty minutes. You make time for your discipline. You find ways, like the Pomodoro technique, to remove and reduce distractions, at least for your set minimum daily study time.

-

Buyer’s remorse: From the perspective of mastery, there’s no place for buyer’s remorse. Your goal is to incrementally get better, and to practice your craft every day. You focus on developing your skills. Instead of comparing yourself to others and worrying about which external course, blog, or book is “the best,” you simply focus internally and honestly on gauging your own skillset and following any curriculum or teacher that allows you to improve. There’s less emphasis on what or who’s “the best” on an objective level, and more emphasis on just gradual personal improvement. You know where your weaknesses lie: just work on tackling and practicing those today, and don’t waste time on tomorrow.

-

Content consumer: A master, almost by definition, is someone who understands and can teach someone else any aspect of the particular discipline they’ve mastered. A master has broken down the numerous necessary chunks that comprise a field into many sub-chunks. When you approach a field from the perspective of mastering it, you can’t cheat or fool yourself. You can’t just consume material without being able to actually understand it. You internalize the material so well that you not only understand its value and place within the field itself, but also how it relates and connects to other fields. Approaching a subject from the perspective of mastery means you are learning the material so you can teach it to someone else, and so that you can create something with what you’ve learned.

Mastery-Based Learning and Software Engineering

What’s a practical example of MBL in real life? Let’s use an example I’m personally familiar with: learning software engineering. MBL is actually even more important for this field, because of the high pace at which new knowledge is created.

There’s such a demand for quality software engineers and such low supply of competent graduates of computer science programs that there are now many schools and bootcamps that teach programming skills to interested students.

With limited time to teach material in a bootcamp to a diverse set of students with differing skill levels, however, some sacrifices will inevitably have to be made. Either the program will go too fast and leave some students behind, go too slow and be a waste of time and money for other students, or have a strenuous admission process to ensure only students with already a certain skill level can enter the program.

Online schools and bootcamps have different pedagogies too. Some profit-driven bootcamps focus on only teaching the most in-demand frameworks, since those are what employers say they want from new hires.

Learning a framework without a solid foundation in object-oriented programming, however, is very much like superficially learning in order to pass a test. Familiarity with a framework, by itself, is not a lifelong skillset. A framework is only a particular expression of software engineering that’s currently de rigueur, and it will most likely be replaced by another within a few years.

Basing your software engineering career prospects on knowing a couple frameworks and libraries is like aspiring to have a pilot’s career by reading and knowing all there is to know about the latest Boeing 777X or Airbus A350-900. Yes, that’s good to know, but how many hours of actual flight have you logged in? Have you successfully flown through a storm, regardless of the plane you were using? Have you flown through a storm using an older plane that didn’t have autopilot or other safety features? That might actually be more impressive.

That’s why some software engineering programs, like Launch School, instead focus on mastery-based learning. Launch School’s mastery-based learning approach is to teach and reinforce the fundamentals of object-oriented programming (OOP), testing, debugging, TDD, system design, networking, database applications, and in general how to write clean, DRY, and maintainable code with intention. Because of its focus on MBL, the program is not confined within a particular timeframe, because every student progresses through the curriculum at their own pace.

The thought process of Launch School is this: investing time in learning and mastering the fundamentals of programming will continuously pay off dividends in the longterm, because you will much more easily pick up, use, troubleshoot, and even create any framework or library you want.

How does Launch School ensure you master the fundamentals? The entire curriculum is based on this. There are required assessments you have to ace before you can move on to the next course, including written exams and technical interviews. There are also many opportunities to review and reuse concepts from prior courses, so everything reinforces and builds on prior pieces. These are all there to ensure you’ve mastered and reuse the foundational building blocks before you attempt to stack more on top.

While other students might be quibbling about or second-guessing whether they should learn Angular or React, or debating how much CSS to learn before moving on, Launch School students have a comprehensive curriculum laid out before them, which progressively teaches them each foundational block they need to know before they can confidently move on. There’s no time wasted second guessing anything or being distracted by the never-ending exterior noise.

I’ve been enrolled for about a month now, and although I have prior programming experience, I’ve been enjoying advancing through the curriculum, and learning a lot nevertheless. I’m finding that my understanding of OOP has been significantly deepened already, and I’m only ankle-deep in the curriculum at this point.

The program has two tracks you can choose from: a JS track that uses Node for the backend, and a Ruby track with Ruby on the backend. Both tracks of course use JS for the frontend, and include the same networking, database, and some other programming fundamentals courses. The Ruby track takes a little longer because you end up learning two programming languages, and is the one I personally chose, partly for this reason.

What’s your take on all of this? Have you found a way to learn a new discipline that worked for you? How do you cut through all the noise and busyness of today’s world? For those software engineering students and practitioners out there, what have you found to be good resources for learning and keeping your knowledge base fresh? For those hiring and managing software engineers, what have you found to be some of the most important characteristics of successful engineers?