Written as a memoir to his son William, who at the time was the governor of New Jersey, Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography offers several valuable insights into the life of one of the most remarkable men of the 18th century.

We all know Franklin as the face that graces our crisp $100 bills. We also think of him as an inventor who discovered electricity, and as one of the founding fathers of America.

The autobiography is enjoyable precisely because of the frank way Franklin seeks to impart life lessons to his reader, to not only share the habits and practices that have helped to catapult him to the topmost ranks of American, British, and French societies, but to also take a critical look at his own weaknesses, and moral failures, so that the reader does not repeat them.

I have summarized my reflections around three main aspects that have stood out to me as particularly relevant to our own life today.

As we will see, it makes complete sense why Dr. Eliot picked this book to start the Harvard Classics series off.

1. Inspiration for diligence and self-mastery.

Probably the singlemost important component of the autobiography is how introspective and self-analytical Franklin was, and the degree to which this self-mastery contributed to his successful life.

According to his recollections, he was protective of his time and sought to never waste it. He writes:

I spent no time in taverns, games, or frolicks of any kind; and my industry in my business continu’d as indefatigable as it was necessary.

In part II of his autobiography, Franklin even elaborates on the practical method he developed for keeping himself accountable, progressing weekly on what he identified as the 13 useful virtues:

| Virtue | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1. Temperance | Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation. |

| 2. Silence | Speak only what may benefit others or yourself; Avoid trifling conversation. |

| 3. Order | Let all your things have their places; Let each part of your business have its time. |

| 4. Resolution | Resolve to perform what you ought; Perform without fail what you resolve. |

| 5. Frugality | Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i. e., waste nothing. |

| 6. Industry | Lose no time; be always employed in something useful |

| 7. Sincerity | Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly; and, if you speak, speak accordingly. |

| 8. Justice | Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty. |

| 9. Moderation | Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve. |

| 10. Cleanliness | Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation. |

| 11. Tranquillity | Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable. |

| 12. Chastity | Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation |

| 13. Humility | Imitate Jesus and Socrates. |

He kept a sheet of paper for every week, with the columns as days of the week, and a row for each of the 13 virtues. At the end of each day, he would put a dot for each injury he committed against that virtue on that day. Every week, he tried to live his life such as to reduce the number of dots on his weekly balance sheet.

2. Autodidacticism and enterprise as a way of life

Aside from his profound commitment to self-mastery, what stood out to me was Franklin’s curiosity and his never-ending love of learning, and his natural sense for what is profitable.

Although he did not have much formal education, having only gone to grammar school–and perhaps because of this–he continued to spend an hour or two every day for the rest of his life on studying something.

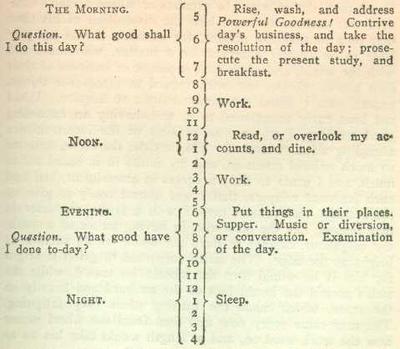

Here’s an insightful look at his daily schedule. We can see the first 2-3 hours of his day were spent on identifying what he would accomplish that day, and on study. At the end of the day, he evaluated how the day went.

Throughout his life, Franklin also embraced discovering and undertaking new things, and developed a keen sense for opportunities.

A particularly memorable anecdote came from the time he was living in England. Franklin tells the story of how he entertained onlookers by his superior swimming abilities, crossing from Chelsea to Blackfriars and

performing on the way many feats of activity, both upon and under water, that surpris’d and pleas’d those to whom they were novelties.

Apparently that feat caught the attention of multiple wealthy families, who began requesting that Franklin tutor their children on his intriguing techniques. Had he remained in England longer, he thought surely he would have opened some sort of swimming school.

3. The Junto, or the importance of keeping good company

Lastly, the autobiography is insightful for showing us how much Franklin valued the company of those who also loved to learn, and who enjoyed teaching and building each other up. He formed and led such a group, calling it the “Junto,” and developed very interesting rules for how the members of this club conducted themselves.

The Junto met regularly, and had so many interesting and productive discussions that the society became the spark for many civic projects like volunteer fire-fighter clubs, night watchmen, and a public hospital.

For more exploration:

| Subject | Link |

|---|---|

| Text itself | https://www.gutenberg.org/files/20203/20203-h/20203-h.htm |

| Original papers of BF | https://franklinpapers.org/framedMorgan.jsp |

| Details on the Junto Club | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Junto_(club) |

| BF’s System of Virtues | https://www.post-gazette.com/opinion/Op-Ed/2019/01/27/Benjamin-Franklin-s-system-of-virtues/stories/201901270010 |