Docker and the Rise of Microservices

What is Docker, What are microservices, and Why should we care?

Courtesy of Ian Taylor, Unsplash

Courtesy of Ian Taylor, Unsplash

As an application attracts more users, the ability to scale becomes paramount. The solution often is to decouple your application and turn your monolithic codebase into multiple microservices. Why is Docker a key component in this new architecture, and what does this all even mean?

I. From Monolith to Microservices

Before the rise of complex and ubiquitous online services like Google, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and YouTube, the standard way to deploy a web application was to have one central codebase that handled everything, from user authentication to interacting with multiple databases to processing payments.

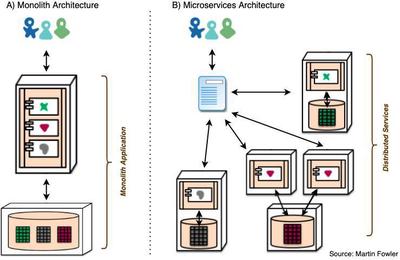

As you can see from image A) on the left above, all the business logic was tightly coupled in the same application, including the logic that handles interactions with database(s).

This behemoth application is called a monolith.

The monolith architecture makes growing and scaling an application more difficult. While a small or even medium-sized monolithic codebase can be copied and deployed on multiple application servers distributed geographically, larger and larger monoliths face challenges that make this process less and less appealing.

1. Requires high level of coordination

There are several reasons why deploying and growing a large monolith is difficult. First, there’s the coordination aspect. Teams responsible for different parts of the application have to make sure that their changes to the codebase are done harmoniously without either creating conflicts with or worse, causing errors to another part of the application.

This requires significant coordination and communication, but also reduces the speed at which updates can be made.

2. Costly redeployments means slower upkeep

Another problem is that every single change to the monolith, no matter how small, requires redeploying the entire codebase. This can make updates so taxing and take so long that they can only happen occasionally, which means responding to changes or adding more features also takes more time.

As the codebase grows, the interval between each update may therefore also grow, as more effort goes into consolidating many updates into the same deployment.

3. Higher learning curve

Another major downside of large monoliths is that onboarding new engineers is challenging and requires more time. In order to understand how to update, fix, add, or otherwise troubleshoot a feature, an engineer may need to understand how the entire system works. If we’re dealing with several thousand lines of code, this is manageable. But multiply this by a thousand, and it becomes almost impossible.

This higher learning curve means that it’s more expensive to hire and add engineers to the team, since they must spend more weeks in training before they can actually start to be productive.

4. One language for all

Another problem of a monolith is that it needs to be written in the same backend programming language–whether that’s Node.js, Ruby, Go, Python, Rust, PHP, Java, etc.

Languages all have tradeoffs: some are better for certain use cases over others. For example, Node.js’s use of JavaScript and its large, prolific community make it ideal for small teams working on small to mid-sized applications or microservices, but its single-threaded V8 engine makes it not as efficient as Go, a master of concurrency thanks to its ability to use multiple channels, and the efficiency gains from being a compiled language.

With a monolith, you are unable to take advantage of the strengths of each language, and you have to accept the entire language for every segment of your application–even if another language might actually be better suited for a particular segment.

5. One bug means the entire application is down

Another problem of putting all your eggs in one monolith application is that if any part of the application fails, the entire system is down.

Yes, you can and should try to handle exceptions as much as possible, but you can’t always predict how your code will behave in production.

When any piece fails, the entire system goes down.

6. Inefficient growth

Finally, the last main reason monoliths are not well suited for growth has to do with the fact that if one aspect of the application needs to be scaled, then the entire application–including parts that don’t handle much traffic–must also be scaled.

It’s like a situation where a family has a two year old, an eight year old, and a twenty year old at dinner, and the twenty year old goes through and finishes his meal very fast. Instead of allowing the twenty year old to help himself to more food, you, the parent, pour an additional 100% more food on every child’s plate.

Some of that additional food is unnecessary and will go to waste!

Wouldn’t it be better to be able to target each child’s needs individually, irrespective of the others?

II. Microservices To the Rescue

Let’s get back to the image above, and imagine that our monolith application in A) handled:

- Showing and searching our company’s inventory to the customer (e.g. the red heart shape in Martin Fowler’s diagram),

- Processing payments for an order (e.g. the green X), and

- Tracking shipments (e.g. the grey blob).

As the diagram shows, all of these might require interactions with a database.

The microservices architecture in B) would instead break each of these services up into separate, independent applications, each with its own database, and each able to receive requests and respond with some information.

These microservices would then be independently scalable, updatable, and could be written in a different language entirely. They can communicate with each other over HTTP through REST-ful APIs, or some other agreed protocol.

The diagram shows, as an example, how the inventory service (the red heart shape) was scaled to two instances, perhaps because more people just search the inventory without actually purchasing. This architecture would allow that, without forcing us to also scale the other services.

Organizationally, teams could be responsible for separate services, and as long as they do not change the format of inputs or outputs of the service, they can push updates without checking with other teams.

And thanks to microservices being independent of each other, even if the shipment service goes down, customers can still look at the inventory and make a purchase.

III. Tradeoffs & New Problems

We can now appreciate why microservices are becoming more prevalent. So we should just convert every application to a microservices architecture, right?

No, of course not. For most applications, from startups to mid-size, a monolith works fine and is probably actually preferable. That’s because just like everything else in tech, the microservices solution now introduces its own set of problems.

Monoliths are much simpler to understand and debug; microservices introduce more complexity. Monoliths tend to be faster, since internal function calls can happen synchronously. Now, as a result of communicating over APIs, the microservices system introduces latency and security issues.

With so many different services, deployed on so many servers worldwide, how do we deal with versioning? How do we deploy systematically? How can we automatically spin up a new instance of a service that we need to scale?

IV. Introducing Docker

We’re finally at a point where we can appreciate Docker.

At its core, Docker facilitates the process of duplicating and starting an application in the same exact configured environment everytime.

A Docker container is an environment in which a bundled application runs the same versions of every layer wherever deployed.

This means that any new application or microservice can now more easily be spun up to run and behave exactly the same way as the original.

A container is different from a virtual private server (VPS) because it does not include the operating system layer, so it’s smaller in size (about 10 to 100X), and more easily deployable. While a VPS might take 3 to 10 seconds to boot on a relaunch, a server running a container can reboot the container’s application packages in less than a second.

Let’s go through a quick overview of the Docker ecosystem and some of the most important components and terminal commands.

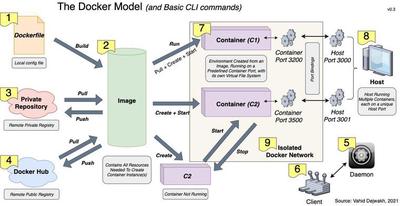

First, a file named [1] ‘Dockerfile’ serves as a config file necessary to build [2] a Docker image.

This image can then be shared remotely via either [3] a private registry (e.g. AWS) or [4] Docker Hub, which is publicly accessible and contains the official images of commonly used software and services.

To pull an image from or push an image to any remote service, and generally to run any number of container(s), the [5] Docker Daemon must first be installed and running on the end machine.

The developer interacts with the Daemon through either a [6] CLI or GUI client.

An image is used to create [7] container instances, which can start and stop to run.

Each running container must be bound to a particular [8] host port.

Containers that need to communicate together can be run inside the same [9] Isolated Docker Network.

V. Summing up

We’ve seen the problems of large monolith applications, and why they are more difficult to scale.

We discussed the advantages of microservices architectures, and why they are growing in popularity.

We also understand the tradeoffs of this new approach to writing software applications, and why monoliths are still probably better suited for small to mid-sized applications.

Finally, we also looked at how Docker facilitates the process of starting and deploying new instances of applications across servers worldwide. This significantly facilitates the movement towards microservices.

I hope it’s been a useful read. Let me know if I left out any other important aspects of this fascinating topic, or if you have any other questions!